On Death

I wrote this a few years ago now, but didn’t post it – at least, not here, anyway. I’ve been thinking about death again a lot recently, for various reasons (’tis the season, after all), so: here it is. Content warnings, obviously, for discussion of death and of human remains, but if you didn’t get that from the title then I’m not quite sure what to tell you.

Death’s a funny one, isn’t it? It comes to us all, but none of us know quite what to make of it.

There’s an age in childhood when we typically become properly conscious of the idea of death, around the age of 7. Child psychologists suggest this occurs at the movement from the preoperational developmental stage, to the concrete operational stage. During the preoperational stage (2-7 years), we tend to see death as reversible, and be prone to egocentrism and magical thinking. Beyond that (7-12 years) our thinking matures, becoming more logical and “grown-up” in its outlook – but before the development of any tempering or cushioning tactics adults use to distance themselves from death, such as, say, belief in a religious afterlife.

For me, this transition manifested chiefly as lying awake in bed at night (something I’m still very good at), trying to understand or conceive of the finality of death. How could I suddenly just stop thinking, stop being? Was it like being asleep? Was it a blackness? Would it hurt? My dad tried to explain that it would be like before I was born; I couldn’t remember that, because I wasn’t there to remember that, and death would be the same. There would be no me to remember. New questions there, a sort of inverted observer paradox: if I was no longer here to observe the world, how could it possibly continue to exist?

(I wasn’t, of course, aware of the observer paradox at age 7; I was an irritatingly precocious little thing, yes, but not well-read enough to be au-fait with quantum mechanics).

Up until a couple of years ago, I hadn’t really known anyone that had died – or no one very close to me, at least. There were hamsters, of course, wept over and then buried in the garden in yellow clover boxes. There was Pete Postlethwaite, and Lis Sladen, who I cried about in the shower. But no one substantial. No one really real.

Then a couple of years ago, I had a sudden triple-whammy in one year. A friend – largely an online friend, but a friend nonetheless, who I ranted at length about risotto with – gone much too soon. A mentor, killed suddenly and unexpectedly in an avalanche. And my grandmother, an ever-curious, ever-pragmatic force of nature.

I went to see the body. Some people told me this was a bad idea; that it is better to remember them as they were than to replace that image with the pale facsimile of death. It’s a personal decision, made for personal reasons. My aunt went; my mother didn’t. My sister didn’t; I did. I don’t know their reasons, but I do know mine. Partly I wanted to pay witness: I wasn’t there with her at the moment of death (my sister was), and I wanted to solidify it and make it real. Mark its passing, mark its presence. My last words to her – hurriedly, as I rushed out of the door to catch a train back to London – were “I’ll see you soon”. So a promise fulfilled, then.

The other reason was one of pure intellectual curiosity. I’d never seen or touched a dead body before, and I felt that it was something I should do. We’re too removed from death, I think, in much of western society. We’ve stopped seeing it as a part of life and severed it entirely from our day-to-day functioning, banishing it into dark corners and hushed tones. Don’t look at the man behind the curtain! There’s still an exception in Ireland, where I’m told it’s still relatively common for the body to lay “in repose” in the front room of the house, and for people to visit it to pay their respects throughout the time before burial. But in general, death is something we don’t want to look at: it’s too unseemly, too macabre. And by refusing it in this way, by making it taboo, we increase our fear of it through its strangeness. At risk of invoking the “read another book!” refrain, and certainly not hugely wanting to quote the work of a particular rampant transphobe, but: fear of a name only increases the fear of the thing itself.

The body was strange. It was and wasn’t her. Her skin was cold, which was expected. Less expected, it was still soft, and baggy about the bones in that particular way of old people’s skin. I was interested in how they’d prepared her, these people who had never met her. They had put on a lipstick that was too dark; apparently they found it with her things, but I don’t remember her ever wearing lipstick. More familiar, they had tucked her handkerchief up her cardigan sleeve, and had it peeking out; an odd bathos for a nose that would never be blown again. I thought it was funny. I cried.

People don’t tell you about the funny bits; the very fine line between grief and hysteria. At the funeral – my sister and I – seated at the very front of the church on pews. I was crying, and trying to cry quietly so as not to disturb anyone else; that horrible crying you trap inside until it causes pressure that you feel trying to shoot out of your eyes and you know will give you an awful and persistent headache later. I also had a terrible cold, and my nose was streaming like a tap. I blew my nose on one of my grandmother’s hankies (borrowed, tucked up my sleeve), trying to do so as quietly and unobtrusively as possible. It made a small noise in the midst of the reverent silence; small and sad, like a wet fart.

The wet fart noise set us off. Those of you with siblings will know the particular way that only they can egg you on, until you’re laughing so hard you can hardly breathe, and you get sent away from the dinner table for once again pulling silly faces at each other through the water jug. The wet fart noise set us off, and once we’d been set off we simply could not stop. Oh, the mortification; a hysterical fit of the giggles at your own grandmother’s funeral. We shook with silent laughter, trying desperately to avoid each other’s eye as we knew it would only make things worse. The guilt, as my mother – mourning her mother – muttered “behave yourselves!” out of the side of her mouth. The knowledge that we couldn’t just run out of the church without passing every pew with the laughter on our faces plain for all to see. The absolute inability to stop any of it from happening. The shame. Oh, the shame.

We didn’t speak of it during the wake. We didn’t speak of it during the drive back to my grandmother’s house. We didn’t speak of it during dinner that evening. It was only after spreading her ashes in the garden (under cover of darkness, so as not to offend Beryl next door) and laughing at the sheer amount there was of this strange white dust, the amount of raking we had to do to try and turn over the soil, the fact that you couldn’t help but breathe some of it in, that I felt suitably prepared to face the inevitable telling-off.

We’re so sorry. I said.

We wanted to stop and we couldn’t. It was awful. We’re so sorry.

“Oh!” my mum said, “That’s my fault – I should have warned you about that.”

She should have warned us about that, but no one ever does. It turns out exactly the same thing had happened to her and my grandmother, at my grandfather’s funeral. She’d been crying and sniffling, and had asked my grandmother whether she could borrow a hankie. My granny – of course – had one up her sleeve, as she always did. She pulled it out. And kept pulling. And kept pulling. In the rush to get ready, she’d somehow managed to tuck a scarf in her sleeve rather than a handkerchief. They got the giggles. They couldn’t stop. And neither could the scarf, which came on and on in reams; like she was a magician at a children’s party doing a magic trick.

I don’t know why I wrote all of this down. I’m not sure what purpose it served, or whether it served any purpose at all. But here we are, in the final paragraph: I wrote it, and you read it. It is something that happened. And death i think is no parenthesis, so on we go.

Garlic Discomfit, or, The Bear in the Kitchen

Note: there are no spoilers in this piece, but there are occasional mild non-specific allusions to particular episodes, events, and character names.

Have you watched The Bear? If you haven’t seen The Bear you should watch The Bear. It’s as near perfect a piece of television as I’ve seen this year, or in the past five years, or perhaps ten. I inhaled The Bear; I watched all eight episodes back-to-back in one evening binge. And I promise you, it will feel like a binge! This is a show about food and you will have to look at a lot of food during it. And if you think that that sounds nice, like a nice thing, like watching Stanley Tucci meander around Italy putting perfect little morsels into his mouth and then exclaiming over them, then you are incorrect – this is extremely stressful food.

When I wrote this tweet I hadn’t yet watched Episode 7, which took me straight back to my Episode 1 opinion but then skyrocketed it to a level previously incomprehensible. Oh my god! Episode 7. The things I could tell you about Episode 7, but won’t, because either you already know or you deserve to go away and find out.

Another thing that I am finding stressful lately is that I am going through a breakup with a boy that I love very much. These things happen. Mostly when I am sad I make soup, and I have been making a lot of soup. But a huge quantity of fresh basil arrives in my fortnightly shop, and I remembered why I ordered it: to make the Family Spaghetti recipe featured in The Bear. And so, because I am heartbroken, and because basil has such a frightfully short shelf life, I make tomato sauce.

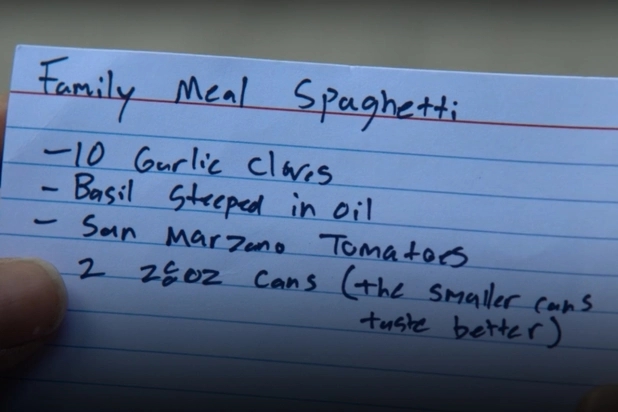

We don’t have a lot to work with when it comes to the Family Spaghetti recipe. What we see of Mikey’s recipe in the show is pretty minimal:

This leaves us with a lot of questions. What do we do with the cloves: do we chop them, mince them, leave them whole? When do we add them to the sauce? How long do we steep the basil in the oil for? How much basil? How much oil? And is that hot oil, or a cold infusion?

Our lead protagonist and favourite strung-out chef Carmy also describes the recipe as “an under-seasoned, over-sauced mess” that “took seven hours to prep”. Seven hours?! Is he being hyperbolous? While I can see the merit in a slow-cooked sauce, I can’t see any way that the above recipe would take seven hours.

We do see Carmy make the recipe, so we can answer some of our questions here, at least regarding his own interpretation of Mikey’s dish. Carmy slow-simmers the garlic with the basil in olive oil, confit-style, with some red pepper flakes (not in Mikey’s original recipe). He puts halved onions (not in the recipe) in butter (also not in the recipe), then adds the tinned tomatoes. Ok, so Carmy makes changes to Mikey’s recipe! He’s an award-winning chef, he must have his reasons; presumably these are to avoid the “under-seasoned, under-sauced mess” he was so disparaging about. I’m presuming that the butter is to act as an emulsifier for the sauce, and that the onions – kept whole like this and removed later – will act as aromatics to infuse the sauce, while avoiding any potential unpleasant pungency.

At this point in cooking Carmy gets distracted because of Reasons, so we don’t see what happens during the rest of the dish. This has caused a lot of agitation on particular corners of the internet who are trying to cook Family Spaghetti; the main question being, should one remove the aromatics from the olive oil before adding the oil to the sauce, or should one blitz the garlic and the basil into the olive oil and then add the resulting paste?

We are forced into our own interpretation of Carmy’s reinterpretation of Mikey’s recipe.

Some have understandably turned to a recipe from chef Matty Matheson, who plays Fak in the show and is also producer, and chef Courtney Storer, who is a producer and the sister of the show’s creator Christopher Storer.

Classic Italian Spaghetti Pomodoro

- Heat olive oil, butter, onion, and a pinch of salt over medium-low heat for 4 minutes.

- Add garlic and stir with a wooden spoon to incorporate

- Add crushed red chili and tomato paste and stir allowing to cook another 2 minutes.

- Add crushed tomatoes. Stir well.

- Turn heat down to low and cook for at least 45 minutes, stirring consistently to keep from burning.

- Add salt and blend until smooth (blending optional).

- Add pasta to salted boiling water and cook until al dente. Add to sauce and cook until pasta’s cooked through.

- Finish with torn basil stirred into the sauce. Top with Parmesan and pinch black pepper.

This is not what we see Carmy do, though: where is the garlic/basil confit?

Over at Buzzfeed, food writer and recipe developer Ross Yoder theorises that “this recipe is inspired by two pretty iconic tomato sauces – Scarpetta’s Spaghetti with Tomato and Basil, and Marcella Hazan’s Tomato Sauce with Onion and Butter, respectively”. We may note that Scarpetta’s recipe calls for the removal of the aromatics from the oil. Yoder changes a couple of elements from what we see Carmy do; he browns his butter and his onions. On the uncomfit question of “to blitz or not to blitz”, Yoder opts to blitz, noting, “I’ll admit that this is the biggest liberty I’m taking with this recipe”.

Mindy Kaling had a go too, and she does it differently again: she CHOPS the garlic, and sautées it in oil before adding the basil. She, too, opts to blitz.

How to proceed?

I have just finished reading Small Fires – An Epic in the Kitchen by Rebecca May Johnson, which is a great book with a lot to say about what a ‘recipe’ actually is. Johnson presents cooking as an active and performative participation between the Recipe as Text and the Cook as Recipient. In one particularly memorable chapter, she goes to war against a paragraph from D.W. Winnicott’s Living Creatively, where he “describes cooking from a recipe as the antithesis of creativity” (Johnson):

“I know that one way of cooking sausages is to look up the exact directions in Mrs Beeton…and another way is to take some sausages and somehow to cook sausages for the first time ever. The result may be the same on any one occasion, but it is more pleasant to live with the creative cook…The thing I am trying to say is that for the cook the two experiences are different: the slavish one who complies gets nothing from the experience except an increase in the feeling of dependence on authority, while the original one feels more real, and surprises herself (or himself) by what turns up in the mind the course of the act of cooking.”

Winnicott

I must admit here that I am prone to something of this way of thinking myself; I get exasperated when, after posting a picture of a particular dish I’ve made online, someone asks me for the recipe. I don’t have one! I don’t cook by following recipes! Except that, of course, I am following recipes I’ve previously read, all of which are responses to some Ur-Recipe, which does not exist, and I am responding to the recipes I have previously read with my own reinterpretation. Received wisdom is still Recipe. Or, as Johnson puts it:

“He is able to define his general model of ‘creative living’ by constructing a neat binary: there is the person who cooks sausages using a recipe, and the person who cooks sausages without using a recipe. There is ‘the slavish one who complies’ (phrasing suggestive of the colonial-misogynistic discourse in which Winnicott has marinated), ‘while the original one feels more real’. The ordering of these binary statements – ‘slavish’ then ‘original’ – is mirrored by the ordering of gender as Winnicott names the cook: ‘herself (or himself)’. The possibility of a male cook is consigned to parenthesis; really, he is in a different room…

The model of creativity that Winnicott produces in response to Mrs Beeton is not of the world, not created in an atmosphere where sausage recipes already circulate like oxygen. Winnicott tries to cook up a theory without recipes, but his reverence for an isolated genius comes out in the cooking and shapes and unappetizing dish. Even when I cook without looking at a recipe on a page, I am always referring to an index of recipes in which I, we, are always immersed. Any ‘new’ dish I make is a composite of fragments I have seen, eaten, heard about in passing and which I repeat in a new constellation, a chimera.”

Johnson

Great book. Recommend. Think Maggie Nelson’s Bluets but make it dinner.

I embark on my reinterpretation of the recipe of Carmy’s reinterpretation of Mikey’s recipe, which was written by Matty Matheson and Courtney Storer, which was possibly informed by Scarpetta’s Scott Conant and Marcella Hazan’s recipes. My recipe is itself informed by Mindy Kaling and Ross Yoder’s reinterpretations, and of course by heartbreak, which brings with it a touch of salinity and a note of bitterness to build a real depth of flavour.

I aim for 10 garlic cloves, but when I have counted out 10 I find that there aren’t many left in the bulb, so I add those too. I am getting better at crushing garlic with a knife to make the peeling easier. I add all the basil from one of my packets, which I’d call ‘a bunch’ but is apparently 30g, and a couple of pinches of red pepper flakes. I add enough oil that the garlic is just about submerged; this turns out to be too much oil, as I am only using one can of tomatoes. It doesn’t seem sensible to use the two cans stipulated by the recipe. I am only cooking for one.

To blitz or not to blitz? I decide to follow the Scarpetta method and remove the aromatics to leave just the flavour-infused oil. My reasoning is that halving the onions and removing them later in order to lightly flavour the tomatoes would be a act of pointless subtlety if you were then going to punch the recipe in the dick with 10 cloves of confited garlic and a load of bitter, blackening basil. After cooling, I set the aromatics aside in some fresh oil so that they can flavour it for later use. I have done Future Nat a solid here.

Meanwhile, I add my halved onions and some butter to a pan, followed by a tin of Mutti tomatoes. I do not brown my butter, because Carmy didn’t brown his butter. I am trying to be as faithful as I can, even if it’s to a fiction. A friend messages me that it looks like I’m simmering boobs. In another pot, I add pasta to salted water.

In Salt Fat Acid Heat, Samin Nosrat says that you should salt your water until it tastes as salty as the sea – or more technically, as salty as your memory of the sea, which is less salty than the actual sea. I remember this whenever I am salting water: as salty as my memory of the sea. When I feel that the onions and the tomatoes have got to know each other, I add half of my oil to the pan. I am careful – oh, I am careful – but it spits at me and burns me anyway. The onions stare at me like two sad eyes: J’ACCUSE!

I am angry at people who haven’t seen The Bear yet, as they might get to see The Bear for the first time. I am also angry with myself, for not paying enough attention the first time, for squandering the time I had by watching with one eye while scrolling through my phone with the other. I should have paid more attention; I should have savoured every moment.

When the tagliatelle is al dente, I remove the onions from the big pan and add the pasta to it to finish cooking. A little pasta water too, because that’s what people do. My sauce doesn’t look quite like it’s holding together – big mood – so I throw in a little more butter. I grind some peppercorns in my pestle and mortar and add a good pinch of black pepper, then take it off the heat and stir in some fresh basil leaves to serve. I heap it out onto a plate and hope to god that this recipe changes my life.

It’s a perfectly fine recipe. I will never make it again.

On Soup & Sanity

Here we are in the Long Dark Autumn of the Soul, and I am once again making soup.

Before I could cook I thought that soup was some ancient sort of magic, an alchemy of flavours and textures that only the chosen few could possibly create. I think perhaps I thought you had to cook it down for a really long time in order for it to become soup, and it would eventually just sort of lose its form and become liquid. Now I know the truth: simply gather some things, chuck them into a pot, and add some liquid and some heat, and then blend it all together. Now you have soup. Sometimes people ask me for recipes for things that I have made; if that’s what you came here for, I am sorry to tell you I do not have recipes. I just chuck some things into a pot. Mostly it turns out ok in the end.

Chorizo and black bean. Black beans to me are the king of beans, and I always have a bit of chorizo somewhere in the fridge because it keeps so long and stretches so far. Chorizo and black beans is my versatile go-to for a stew or a soup. The fat in the chorizo renders down, giving the results a smoky depth of flavour while only using a relatively small amount of meat. It’s forgiving enough to take almost any sad old leftover veg, particularly roots, greens, and peppers, and robust enough to handle a good heft of spice if you’re in the mood. Sometimes I make it vaguely mexican in style (not in a Great British Bake Off way, I promise!), with ground coriander and cumin, a good squeeze of lime, and some sour cream, fresh coriander and jalapenos to garnish. Sometimes I do it US baked beans style, with brown sugar or maple syrup, barbecue sauce, and a bit of mustard and vinegar. Mostly I do it like brazilian feijoada; slow-cooked until tender so that the beans meld with the pork, with lots of garlic and a pinch of chilli flakes. Always, but always, I do it with a heavy helping of smoked paprika.

If there were one kitchen gadget I would recommend buying, it’s a hand blender. If there were two, it’s a hand blender and a pestle & mortar, because having a pestle & mortar makes you feel like a cool hedgewitch and whole peppercorns keep much better than ground.

Now that I understand the secret of soup, which is that there isn’t one, it’s something I turn to as soon as the leaves start to turn; even this year, which remained stubbornly 21 degrees C until the end of October. The garden is confused by the weather, and so am I. It’s November, and the roses are still in bloom. The blackberries fruited back in June. The long heatwave in the summer and its accompanying drought meant it was late in the season before seeds got any water; now I have tomatoes and potatoes and a butternut squash coming up. They won’t bear fruit, but I was glad to see them anyway after months of scorched ground.

Spicy roast butternut. I don’t often bother roasting vegetables before I put them into the soup pot, because I’m quite lazy, but if you have the extra time and inclination then it’s worth it. Roasting vegetables helps to bring out their natural sugars, so you’ll end up with a sweeter, smoky depth of flavour that suits the season. If you don’t have the time and inclination then don’t; it’ll still be tasty. I roasted butternut squash and red onions here then went a bit Ottolenghi on its ass with fermented lemon, sumac and smoked paprika, plus fresh parsley and goats cheese to garnish. Plenty of black pepper.

(If you’ve never made fermented lemons, and I’m aware that fermenting your own lemons sounds very wanky, it’s pretty easy and gives you an off-the-shelf way to add a deep, dark, citrussy twist to tagines, soups and salad dressings. It’s also great blitzed then mixed into mayonnaise as a fancy dip. Once you’ve got a big jar on the go you can just top it up as it depletes. When life gives you lemons….put them in salt.)

My mental health has been a bit all over the shop lately, and I say that as someone who’s mental health is rarely even in the shop. My mental health is more one for occasionally glancing into the shop and then absolutely nopeing the fuck out of there. My mental health is on my sofa ordering supermarket delivery because it can’t handle the shop. My mental health is standing in the drinks aisle having just dropped and smashed a bottle of wine because it was trying to carry two of them at the same time as a lot of snacks because it was feeling sad and now everybody is staring and I’m not sure whether I’m supposed to pay for something I haven’t yet bought but have now broken and the shop assistants don’t seem sure either although they do certainly seem irritated.

Italian courgette and parmesan. This is a family favourite to use up a glut of courgettes or marrows, and one of the few things in life I do follow a recipe for. It sounds simple, but the end result is far greater than the sum of its parts: garlic, cream, chicken stock, courgettes, basil, parmesan, white pepper. The pepper always has to be white; don’t be tempted to sub in black pepper here. I have a friend from higher up the class ladder than me who says he would never touch white pepper, but he is wrong; to my mind it is particularly good friends with white beans and light greens (your cannellinis, your butterbeans, your haricots; your broccoli, your spinach, your courgette). Do make sure to use about a third more parmesan than the recipe suggests. Life is short, and so is the daylight.

I think a lot of us who have dealt on-and-off with depression and its kin have a similar approach to the dark times; which is to say, we do what we can, when we can do it. Ella Risbridger’s recent blog post on Broccoli Gnoccholi really resonated with me on this; like her, I have a list of ways to try and stay on the right side of sane when things are getting a bit hairy. These are all things that I am terrible at sticking to doing, but that I know make a difference (not a lot of difference – but just about enough, as long as I stay lucky) when I do them. Going for a silly little daily walk. Watering the plants, who are dependent upon me but ask for very little. Cold water showers. Taking my meds (Team Citalopam). Doing meditation. Attempting yoga. Peddling on the exercise bike while listening to Radio 4. Reading. Lifting weights so that my knees feel stronger and less shaky. Keeping my space tidy when I can. Crunching about in the woods, naming the plants and the mushrooms as I go and gathering some of them sometimes to eat. Trying to go into the office one day a week, to remind myself that I am a capable adult human with a job that I am in fact mostly not terrible at.

Roast chestnut, apple and carrot with bacon and thyme. Chestnuts and apples both love pork, so I did this with bacon and pork stock. I put greek yoghurt in to give it some creaminess, because that’s what I had in the fridge, but actual cream would be better here. The carrots don’t have to be carrots; they could be sweet potato, or butternut squash, or even pumpkin if you have some flesh left from hallowe’en. Acorn squash or delicata would be the ideals here, for a little more earthiness, but basically as long as it’s orange then you’re golden. Bay leaves. Shallot. Black pepper. Thyme. I added a good splash of apple cider vinegar to cut through the sweetness and brighten things up a bit (“your dish needs acid”). This soup gets extra Autumn points because I foraged the chestnuts myself, and because I fried some chestnut crumbles up in the bacon fat as makeshift croutons in a move I can only describe as “inspired”.

Cooking is the other thing that I do to stay broadly on the right side of sane. Again, partly I think it makes me feel like a competent human adult: “Look, I can make a sustaining and reasonably tasty meal to keep myself alive!” It reminds me of the colour and variety of life at times when I’ve lost track of it a bit; the bright, popping red of tomatoes, the sour fragrance of lemongrass, the glug of olive oil from a glass bottle. Mixing and matching ingredients lets me feel like I have some sense of creativity and control, even if it’s only within the four walls of my very small kitchen. Two walls, really; it’s a galley kitchen.

Above all, it’s meditative; the actions are repetitive and familiar. And soup is, I think, one of the most meditative meals to make: stripping the brown skin from an onion to expose the white pearl within, chopping and dicing the vegetables, grinding and grating, stirring, stirring, stirring. It takes effort, but it’s a relatively easy and low-energy kind of effort, and it takes time, but it doesn’t take too much time. You don’t have to use your brain much, you just have to gather some things, and chuck them into the pot, and add some liquid and some heat, and then blend it all together. Now you have soup. You may not have sanity, but at least you have soup.

Long Distance

I miss the boy I love – of course

He isn’t quite exactly mine

But fingers slot as though he were

From time to time, from time to time

And every day I do my job

(He has a world outside of me)

I make my bacon on the hob

(And so do I – alcohol, tea,

And books and friends and slow-cooked stews

And woodland walks, and rolling news)

But time goes slowly when you wait

The key in lock. The garden gate.

I wait, because he’s out there still

Setting bacon on his grill.

when will my concept of “linear time” come back from the war?

Time’s gone weird, hasn’t it? Hasn’t time gone weird? I’m really struggling with it at the moment. I don’t know what day it is. I’m not sure whether it’s day. It’s still March 2020. It’s 2022 in 4 months. It’s been Wednesday for years. I’ll be dead soon. There are no weekends, and no weeks. I’m always at work. I’m always at home. Nothing has any edges. Time is not so much a flat circle as an amorphous blob, a vague nebula I hover suspended within where things that happened last year feel like yesterday and things that happened yesterday feel like last year.

So please, I beg of you: when will my concept of “linear time” come back from the war?

I think I thought that after lockdown was lifted, and things went back to some degree of “normal” – whatever that is – time would snap back into place and the days would resume their usual progression, Monday to Tuesday to Wednesday and so on. It’s not that I’m particularly attached to that order; it’s more that I feel like I blinked and lost a year, and then I blinked and lost another 9 months. And now I’m filled with existential dread that I will blink again and I’ll be 50 and then I’ll be 80 and still I’ll just be sat here, in my house, drifting from the bed to the desk to the sofa to the bed, and then I’ll be dead. I’m not scared of death, you understand. I just didn’t expect it to run up behind me in this aggressive manner.

When I was at university I used to work part-time at the local hospital as an audio typist, writing up notes from the consultants and the nurses on their patients. After I had written up the notes I would add them to their cardboard files, and then I would put all the cardboard files on a trolley and push them to another part of the hospital. It was a good job for me because I like typing, and I’m very fast at it, and also when you’re plugged into an audio cassette there’s no pressure to make conversation with other people in the office or pretend that you’re a nice person. The department I worked in was Psychiatry for Older People, so there was some pretty unsettling stuff in the notes, which I also liked.

When you’re admitted to hospital for psychiatric reasons as an older person you have to fill in a Mini Mental State Examination – MMSE – to assess your competency. One of the questions in it is what the date is. I was always astonished at this as a measure of mental competency. I remember thinking at the time, that I – as a feckless student – didn’t always know what the date was, and that once I was elderly and retired I would absolutely have no reason to know – indeed would actively seek not to know. And on that basis, I could be judged mentally incompetent or unsound.

(I should add of course that the MMSE is not a “one strike and you’re out” deal. The situation’s a lot more nuanced than that.)

Our concept of time passing is driven by external stimuli: our diurnal rhythms chart the rise and fall of light levels, we go for our lunch break at roughly the same time every day, we leave the office at the same time every evening, we know that on Thursdays we have football practice or choir practice or book club, and on Fridays we usually go to the pub. We put something in our calendar for two weeks’ time, and we look forward to it, and after two weeks it happens, and then we put another thing in our calendar for two weeks’ time. But what happens when we decrease external stimuli, or get rid of them all together? What happens is this: time goes weird.

In 1962, French geologist Michel Siffre carried out a series of experiments where he sent people into dark caves for months without clocks, calendars or contact. Without the stimulus of natural light, subjects fell out of sync with our usual 24 hour day/night cycle. Some fell into a 48 hour rhythm, staying awake for 36 hours and then asleep for 12 (researchers have since discovered this is the pattern most people fall into without external input). At the end of the experiment, many subjects expressed surprise, thinking they had weeks or months left. When Siffre himself left the cave, he believed it to be August 20th – it was in fact September 14th, 25 days later. Conducting tests with his team on the surface, they discovered it took him five minutes to count to what he believed was 120 seconds.

And earlier this year, while many of us were still in lockdown indoors, 15 people were isolated in the Lombrives caves in France for 40 days and 40 nights, with no updates from the outside world and no daylight. Again, they lost their sense of time, with participants estimating their time underground at between 23 – 30 days.

While we thankfully haven’t been cut off from daylight, the external stimuli we are exposed to has nonetheless decreased. Things we might classify as ‘events’ are fewer and further apart, and without as much drive to stick to a strict structure or routine in our days and weeks, we are missing many of the waymarkers that usually chart our paths through life.

In his paper ‘The Inner Experience of Time’, researcher and author Marc Wittmann (author of Felt Time: The Psychology of How We Perceive Time [MIT Press]) notes that, “Although we doubtless have a time sense, our bodies are not equipped with a sensory organ for the passage of time in the same way that we have eyes and ears—and the respective sensory cortices—for detecting light and sound. Time, ultimately, is not a material object of the world for which we could have a unique receptor system. Nevertheless, we speak of the perception of time. When we talk about time (‘an event lasted long’, ‘time flew by’), we use linguistic structures that refer to motion events and to locations and measures in space; a further indication that time itself is not a property in the empirical world.”

Our tendency to describe time in terms of space, place, and motion, makes intuitive as well as scientific sense: time is a property of space, and the two are bound together in physics to form the four-dimensional model we refer to as ‘spacetime’. Less scientific, but I think still intuitively true: the fact that our movement in and through space has been severely restricted over the past 18 months has had an impact on our perception of our movement in and through time. We physically haven’t travelled through space very much, so we feel like we haven’t travelled through time very much either, and then are surprised when we look up to find it’s next month.

I don’t know how to fix this, how to hold onto the time that’s running between my fingers. There are events in my calendar again, but I can no longer meaningfully differentiate between the ones that are next week and the ones that are in August 2022. Should I fictionalise a strict routine to stick to, to give myself new rhythms? Should I restart my silly little daily walk, to try to trick my brain into thinking I’m moving? What do we use now as waymarkers, in a world that’s lost its way?

I started writing this ten minutes ago and now it’s two hours later.

Track and Trace

I went on one of my silly little walks yesterday, and I bring back breaking news from the limits of lockdown: here is Spring. Here is Spring, and there are snowdrops peeking out from inside their little hoods, and carpets of yellow and violet crocuses, and the occasional frankly indecent splash of daffodillian sunshine.

These signs of life – always welcome at this time of year – are even more welcome in a time when it’s hard to find any other semblance of life around you. Walking on the street is the closest we get to other people now, but even that feels hurried, illicit, forbidden. I hide behind my mask, keeping a safe distance as long as the pavement allows. When the pavement doesn’t allow, I avoid looking at passers-by altogether, as though eye-contact increased the changes of contagion. Any snatches of overheard conversation feel like contraband, and I smuggle them into my pockets like pebbles, hoping that no one notices I’ve broken the rules.

Because the people I pass feel like inaccessible ghosts, I find myself instead seeking connection by looking for evidence of other humans having interacted with their environment. Like a tracker in the forest I trace their prints and spores, reading lives and stories into any sign I can find. I pause to hungrily read every plaque or notice I see, as though they were cultural exhibits: a litany of lost cats, unending rainbows for NHS workers, planning permission for a community mural. I even stop to read the menus outside pubs, imagining what I’d pick, imagining the inside warm and filled with people. Placards on benches. Peeling protest posters. Snippets of graffiti: Gaz woz ere. Who is Gaz? What was he doing? Where is he now? I don’t know, but the tangible fact remains: there was a Gaz, and he was here.

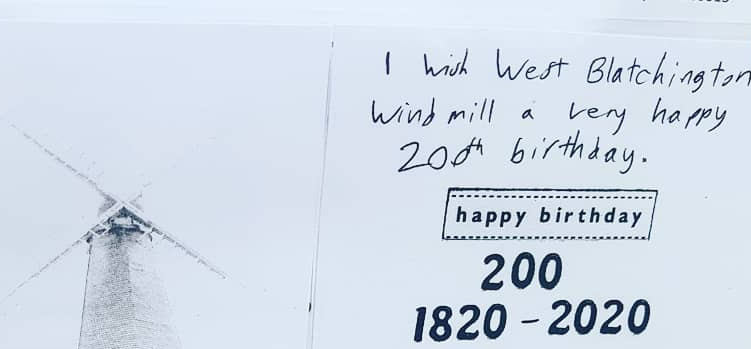

On my silly little walk yesterday I went to visit a windmill. It’s a local windmill, and it seemed absurd that I hadn’t been to see it, so I did. I couldn’t go inside, so I walked around it, admiring the large millstone by its door, being pleased that the street names around it echoed its farmland history: Fallowfield, Downland, Meadway. I noticed that there was a road running directly south from the windmill to the coast, and that there was a direct line of sight running from it out to the coastal wind farm. All day long the windmill and the wind farm face each other, of a kind but out of reach. Does he long for his seafaring brethren, I wondered? Is he lonely, cut off from the flock, holding tight to the land while they frolic together out in the waves?

I discovered I wasn’t the only one guilty of anthromorphising a windmill: on its door, a noticeboard, with a birthday card pinned up. It was 200 years old last year. Who heeded the windmill’s birthday and sent a card? Someone like me, I imagine, who thought it might be lonely. Someone lonely.

I tell myself I ought to seek connection and escapism through reading: after all, there’s a thousand worlds out there, and I have a simple way to access them literally at my fingertips. But the only books that I can manage to read at the moment are those about other lonely people: the disconnected, the disaffected. I read Hermann Hesse. I reread Jean Rhys. I plough through memoirs of people struggling on the outskirts of society, addicts and depressives and obsessives. I listen only to the saddest songs, and ask myself that unanswerable question: what came first, the sadness or the songs?

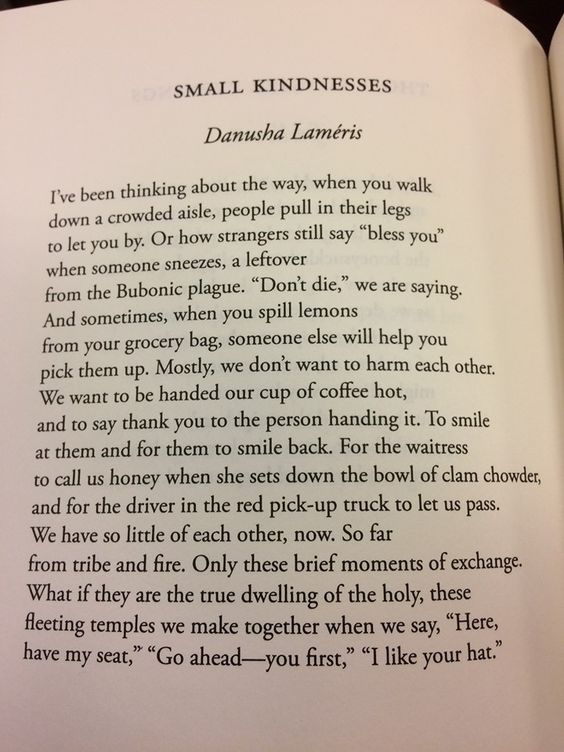

Poetry, though: poetry helps. I find myself seeking out the sort of poetry that offers tangible goodnesses, rooting me into the physical world and helping me celebrate the small things each day: the sudden brightness of an orange, a bird alighting momentarily on a chimney stack, the skin-opening shock of a cold shower. Like this, by Danusha Lameris:

This one also reminds me that it’s ok to mourn what we have lost over this past year: all those minutiae, all those little transitions and transactions that make up a life lived. They may be each be a tiny thread, but they are the stuff that make up the tapestry.

It also reminds me that there are things to celebrate here and now. I can hand myself my own cup of coffee, and take joy on each warm dark sip. I can go for my silly little walks, and trace the signs of other people through the landscape, and know that the days are getting lighter and the end is in sight. I can admire the warm indigo of the dog violets, and their heart-shaped leaves, and marvel at the fresh green shoots as they push their way out of the ground: so fragile, so persistent.

It’s Spring. I like your hat.

On Shutting the Fuck Up

Stuck inside in lockdown

And you can’t escape the noise

There’s a man getting his cock blown

There’s a woman using toys

There’s an angle grinder out the back

A strimmer out the front

Who puts the ‘I’ in DIY?

It turns out, every cunt

Next door have daily gatherings

Of blokey football men

I listen to their blatherings

Til three, then four, a.m.

From downstairs constant music

Comes pulsing through my bed

I put some tissue in my ears

A pillow on my head

Outside the city rages on

An ever-thrumming hive

As each declare with all their lungs

Thank god! I’m still alive

On the Other Side

Nobody does DIY unless they think there’s a future

And the man next door to me is doing DIY

Drilling and stripping. Soldering on.

After all this is over, he thinks:

We shall have a nice kitchen.

And perhaps friends will come round – perhaps family

To admire the handiwork previously only glimpsed through screens

Coo over the new tiles: a carefully-chosen verdigris

Pleased by how they set off the persimmons, plump in the bowl

Perhaps there will be herbs on the windowsill

Warmed by the sun and then scattered on tomatoes

Something Ottolenghi.

Olive oil. Perhaps a bottle of red wine.

Perhaps there will be air full of chatter

Children and dogs under foot, a casual chaos

People who haven’t seen each other in too long trading secrets

Perhaps recommendations swapped: this book, that film

Perhaps an empty chair which should have been full

Moments of silence where jokes would normally have been

An oft-told anecdote; missing.

More wine. A toast.

Baklava from the shop next door, sticky fingers

After all this is over.

The Tenacity of Hope

After an impressive run of absolute awfulness, this year appears to be pulling out some actual good news out of the bag right at the last minute. But it’s very hard not to anthropomorphise 2020, which seems to delight in confounding expectations, piling misery upon misery, and all in all just being an outright absolute prick. Like many among us, I’m finding it difficult to trust good news; not least because there are still far too many confounding variables to count. I worry about things going wrong. I worry about what comes next. I worry about the knowns, the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns.

Those that are unlucky enough to know me will know that I tend towards cynicism as a starting-point. Sarcasm is my default mode. Terms that have been used to describe me include ‘spiky’, ‘arch’, ‘intimidating’, and ‘waspish little bitch’ (thanks, M*lo Y*annopoulos! I bear that last with pride). 2020 – and, let’s face it, the last four years – has offered me plenty of opportunity to practice and exercise this cynicism. Eventually, I simply started to assume the worst outcome in all cases, rather than hoping things might change or get better. This wasn’t difficult; we’d all been burnt before, when it comes to being absurd enough to hope. Hope is silly. Hope is frivolous. Hope is, most of all, dangerous.

And now I accidentally have some of it.

It’s the hope that kills you, they say. It gets under your skin, burrows right down into you and then enters into the bone marrow. It’s like a cancer of our own choosing: once we have allowed one cell to be infected, it will multiply and multiply, all while your body fails to recognise it as a foreign object and simply accepts it as one of its own. Once it’s in the system, that’s it; it’s as much a part of you as you are. Encoded into your RNA, nestled in your gut, running up and down your backbone.

So what do we do with hope, this alien invader, this meddling interloper that poisons our every day? Like all diseases, we learn to live with it. To sit with it, and with its shadow-self, fear.

There’s a burgeoning movement online called ‘hope-punk‘: the idea that, in the world we are living in today, the very act of having hope is a radical act. Hope-punk is there in community organisation, in collaboration, in care. It’s a refusal to be resigned or cowed or to give up, and instead to fight: but to fight not with spite, but with kindness, compassion, and gentleness. It’s also the idea of proactively finding joy or delight in the small things every day: hot buttered toast dipped into a warm vat of autumnal soup; leaves caught suspended for just a moment in a miniature tornado; the silhouette of chimney stacks against the skyline. Taking the time to notice these things and find moments of care and calm makes us better equipped and more resilient for the fights ahead. It’s part mindfulness, part self-care, part political action: to not only allow yourself to have hope, but to proactively create and foster hope.

I am trying to learn to live with hope, although it frightens me. I am trying to invite it in; to make a space for it on the sofa next to me as I doomscroll through my social media feeds, to take it out on walks with me on a short leash, to test the waters with it as I wade out into the Brighton sea (which is, at this point, very cold).

My hope, of course, will always be tempered. We’ve had a slew of good news over the past week. Is any of it perfect? Oh no it’s not perfect; it is far from perfect. But perfect isn’t what we’re striving for here. What we’re striving for is ‘ok’. What we’re striving for is ‘bearable’. Because things haven’t been, for a long while, and though you get used to it and you manage to carry on with your day, it sits in your chest like a rock. Every day you haul that rock up the hill of simply getting up and looking at the news. What’s happened now. What’s happened now. What’s happened now.

Sometimes what’s happened now is something not terrible.

So I will live with my hope, and I will temper it. I will temper it like I temper my spices: tipping them into hot oil until I extract their fullest flavour. I will take a moment to admire the deep burnt red of the chilis, the warm sunset orange of the turmeric, the tiny joyful pops of the cumin and black mustard seeds. I will open the window to let in fresh air, and turn on the radio to keep me company against the darkness outside. And I will make myself a meal: one that will warm me on the inside and sustain me, at least until tomorrow.

Things I’ve learned in between lockdowns

Back in May, which now seems so distant it could be another planet, I wrote about things I’d learned during lockdown. This was a sort of a stock-taking exercise; something that many of us were doing, to try to find the positives during what will forever be referred to as Unprecedented Times and reflect upon this strange period. “Lockdown lends itself to a certain type of introspection that forces the hand.” We told stories extolling the virtues of a slowed down life, of finding hope in growing things and making things and baking things, in using isolation – somewhat counter-intuitively – to reconnect with other people we’d lost touch with, as well as to reconnect with ourselves. Oh, what sweet summer children we were.

We’re in a very different world now and this is a very different blog post, because it’s increasingly difficult to find the positives here. The week before we enter into our second national lockdown here in the UK, what was initially a novelty has now become gruelling endurance test. What was once a national mood of “coming together” to provide mutual aid, concentrate on the importance of community, and changing our behaviour in order to protect and provide for those around us has soured. It would be easy to blame this on lockdown fatigue, and that’s certainly part of the equation. But largely, I think, it lies in broken promises and enormous bungling by our government.

We went into the initial lockdown in good faith. We believed (or at least hoped) that the time we spent isolating away from our friends, our family, our lives, would be well spent: creating action plans that would allow us to do things safely, if in a minimised fashion; developing a “world-beating” test-and-trace service (though why it would need to be world-beating remains a mystery to me – I want the world to come out of the other side of this virus, not just my country); providing support for workers and small businesses that needed it. Instead, that time has been squandered, the advice of scientific experts ignored, and we’re now heading back into a second national lockdown on the back of the inevitable second-wave.

So, what did I learn between lockdowns?

If you’re not incandescent with rage, then you’re not paying attention.

“World-beating” apparently means “national embarrassment”

To create our “world-beating” test and trace system, the government appointed their pal Dido Harding (who oversaw TalkTalk during its breach of privacy data, and so perhaps should not be in charge of anything including personal data ever again) to run this centralised project, along with a board that shockingly contained only one health expert, no data scientists, no social or behavioural scientist, no NHS logisticians and no behavioural scientists.

For inexplicable reasons, they decided initially to try to create a test and trace service alone without drawing upon existing technology and expertise. Weirdly, this didn’t work, and they ended up going back to the drawing board to use the technology we should have used in the first place, then creating an app that can only be installed on modern phones, not bothering to push its release to the public via any particular type of announcement, providing no or limited training to contact-trainers, promoting teenagers in those contact-training call centres against their will to provide health advice or bereavement support with little or no training, and failing to make said call centres COVID-safe. It’s now been shown that the system fails to reach almost 40% of close contacts of people who have tested positive, and the app fails to warn users who may have been exposed to self isolate, Development of the test and trace service was meant to cost the taxpayer 10bn. Current estimates look more like 35bn.

This is without getting into the issues with relying on an app anyway: those most vulnerable to the virus are the elderly (who often don’t have mobile phones, or are more likely to have an older phone), and communities – often BAME – who work in roles deemed “essential” (cleaners, takeaways, delivery drivers, care roles, etc) which are paid at minimum wage (and so are, once again, more likely to have an older phone).

The government is using the pandemic as an excuse to grant huge contracts to privatised companies and individuals with no due process or transparency

We already saw this happening under Brexit, with the government awarding £18m to Seaborne Freight as part of no-deal preparations – a company with no experience in channel freighting, and indeed no actual ships. But it’s become rampant during the past year, and always (funnily enough) to companies associated with members of the Conversative party, or associated with large tory donors. I won’t list the ways, because George Monbiot has already done it, and done it better, here.

Our government priorities our productivity under capitalism over our lives and wellbeing

Now that the genie has been let out of the bottle and lockdown lifted, they’ll find it hard to convince people to be compliant once more given how the rules during and in-between lockdowns have so clearly demonstrated where the government’s priorities lie. They didn’t allow us to meet with our friends and family indoors, but they told us to sit indoors in an office. Funerals during the first lockdown had to be held over Zoom, with people unable to meet to grieve together or spend final moments with loved ones, while Dominic Cummings – positive with COVID, and symptomatic – swanned up and down the A1 for a little picnic at Barnard Castle. I notice they’ve been sure to cover this in the second lockdown rules: we aren’t supposed to travel or to go to our second homes in the countryside (because of course we all have second homes in the countryside), unless it’s “for work”. So if you’re working from home, and you need to work from another home, which happens to be near a popular tourist spot, go for it I guess.

They refused adequate support to the arts, which have been so critical to keeping us all entertained during the lockdown, and forced those they did give support to to cravenly thank them publicly. Please sir, can I have some more?

They sent students back to university, at the totally reasonable cost of £9,250 a year in tuition fees, failing to tell them in advance that there was often no intention of lectures being carried out face to face, then locked them inside halls where there had been outbreaks of coronavirus (SHOCK!) and charged them £17.50 a day for delivery of food, or continued to make them pay rent on empty rooms.

They sent pupils back to school where they must now sit in cold rooms with all the windows open all day, as the weather gets colder, and must sit in their kit all day if it’s a PE day, even if said kit is damp from doing PE outside. My cousin has athletes foot now, cheers everyone.

They literally gave us money to eat out and “save the economy”, in a scheme which cost the taxpayer 522m and has now been shown to have contributed to the second wave. Meanwhile they refused to pay for school meals over the holidays to our most vulnerable children, which would be cost a mere 120m, leaving already under-supported local businesses to step up and causing even more people to turn to food banks (data from The Trussell Trust shows that over half of households that needed support from a food bank in the Trussell Trust’s network in April 2020 had not used a food bank in the network previously, and predicts there is likely to be a 61% rise in need at food banks in the Trussell Trust’s network this winter).

By the way, you can sign up to donate to The Trussell Trust here. I make a monthly donation. YES, I’M VIRTUE-SIGNALLING. KNOW WHY??? BECAUSE VIRTUES ARE GOOD THINGS TO HAVE, AND SIGNALLING THEM CAN SOMETIMES ENCOURAGE OTHERS TO ALSO HAVE THEM. I don’t believe food banks should exist, and the fact that they do is a failure of our government and our society, but in the meantime we work with what we have while we lobby for change.

Everyone except me goes to the cinema a lot lmao WTF????

Mates. What is this thing with cinemas?! Don’t get me wrong, I love films, but the CINEMA??? A place where you pay an obscene amount of money to sit in a dark room listening to a load of people you’ve never met all eat the noisiest varieties of snack possibly available? Seriously, whoever decided that popcorn – a word with the literal word “pop” in it – should be the go-to snack for movie-goers has a lot to answer. And whoever it was who decided cinemas should also increasingly start offering nachos deserves a few stern questions at the same time. Why are there even adverts?! YOU’VE PAID IN. I subscribe to streaming services so that there AREN’T adverts. At some point, you’ve all been brainwashed into thinking “the cinema experience” is some holy and profound thing, when in fact it is stressful and irritating and overpriced. Much as I had absolutely no idea you were all getting your hair cut every 5 minutes, I had no idea you were all going to the cinema so often. You are all baffling. I am baffled.